The Problem of Cupping Notes, the Problem of Realism, and Andy Warhol’s Solution for Both

I have recently been asked how I come up with my cupping notes. Do I really taste things like “musty, cocoa dusted over-ripe strawberries,” “apricot syrup,” “sweetness like meringue over cooked bananas,” “damp pipe tobacco,” “leather soaked in apple juice,” and so on. My answer for this probably qualifies as a tangent (hence my necessary category: “Ramblings”), but I have attempted to illustrate the problem, and perhaps the solution, with analogy from art history and theory. If you just want the short answer, skip to the last paragraph.

Art always serves as a sort of prophetic voice in culture. It is, in many ways, an interpretation of culture itself. Art often gives us an illustrated depiction of, among other things, the worldview of a person, and often that person is acting, consciously or unconsciously, as a representative of the people to whom he or she belongs. In the latter half of the 19th Realism dominated the art scene. Realism in visual arts was borne out of a reaction to Romanticism, and in particular a reaction against Romanticism’s dislocation of beauty outside ordinary life (fn. 1). Realism was, therefore, characterized by its depictions of ordinary, everyday life, on the premise that “it [was] necessary for the mysterious beauty which human life accidentally puts into [everyday life] to be distilled from it” (fn. 2). This meant that all expressionism, idealism, romanticism—anything subjectively imposed on the portrait by the artist—distracted from the true beauty that could be found in an ‘objective portrayal’ of something accessible to everyday life. And thus realism became a sort of obsession with ‘objective reality’. Beauty was not in the eye of the beholder—just the opposite. Beauty was objective, to be found in the external world. Perspectives and interpretations were irrelevant. Beauty was fundamentally objective. So here we have Gustave Courbet’s painting, “Dead Deer.” Behold…the beauty…

I’m no art scholar, but I find this not only to be an affront to how we experience beauty, but to how we experience the world. Realism seems to assume that beauty exists as an object to be observed and appreciated as such. There can be no expression of beauty, as though we could either contribute to its existence or ourselves locate it in a certain perspective of an object, otherwise neutral. Beauty exists with or without an eye to behold it, or so it went. Expressionism, a reaction against Realism (and Positivism), was aptly given its name because it found beauty (or perhaps angst—another topic altogether) through subjective expression of the artist’s [or the artist’s depiction of the human] experience, and not reality as such. The pendulum has had been driven from the ends of the earth to the center of the heart, but unless we deny what we know to be common experience, doesn’t life itself seem to exist between these two poles? Are we not constantly being struck from the left and the right by the crises of the world and the anxiety of our souls?

I’m no art scholar, but I find this not only to be an affront to how we experience beauty, but to how we experience the world. Realism seems to assume that beauty exists as an object to be observed and appreciated as such. There can be no expression of beauty, as though we could either contribute to its existence or ourselves locate it in a certain perspective of an object, otherwise neutral. Beauty exists with or without an eye to behold it, or so it went. Expressionism, a reaction against Realism (and Positivism), was aptly given its name because it found beauty (or perhaps angst—another topic altogether) through subjective expression of the artist’s [or the artist’s depiction of the human] experience, and not reality as such. The pendulum has had been driven from the ends of the earth to the center of the heart, but unless we deny what we know to be common experience, doesn’t life itself seem to exist between these two poles? Are we not constantly being struck from the left and the right by the crises of the world and the anxiety of our souls?

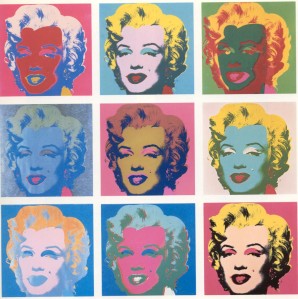

Andy Warhol’s art perhaps represents a healthy critique, and perhaps a healthy balance, to these opposing perspectives. As you can see from his famous piece, “Marilyn,” Warhol seems to communicate something both objective and subjective in this piece. All of the portraits of have a definite, objective referent (Marilyn Monroe) though they are depicted through various ‘perspectives’; all of them are meant real and yet none of them are meant to look ‘real’; all of them are slightly the same and yet all of them are slightly different, one from the other. This illustrates the many perspectives through which the objective world is both perceived and expressed. We do indeed exist in an objective world, but it is a world seen and experienced through many different eyes, worldviews, and histories, and Warhol recognized this. In the words of Glenn Ward, Warhol’s art, which existed somewhere in a tension between abstraction and representation, “is open to the plurality of experiences and understandings that different groups can invest in images” (fn. 3).

Andy Warhol’s art perhaps represents a healthy critique, and perhaps a healthy balance, to these opposing perspectives. As you can see from his famous piece, “Marilyn,” Warhol seems to communicate something both objective and subjective in this piece. All of the portraits of have a definite, objective referent (Marilyn Monroe) though they are depicted through various ‘perspectives’; all of them are meant real and yet none of them are meant to look ‘real’; all of them are slightly the same and yet all of them are slightly different, one from the other. This illustrates the many perspectives through which the objective world is both perceived and expressed. We do indeed exist in an objective world, but it is a world seen and experienced through many different eyes, worldviews, and histories, and Warhol recognized this. In the words of Glenn Ward, Warhol’s art, which existed somewhere in a tension between abstraction and representation, “is open to the plurality of experiences and understandings that different groups can invest in images” (fn. 3).

At this point you may be asking yourself, “What in Sam Hill does this have to do with cupping coffee?” Well, it’s a bit of a stretch, but the point is this: when we are cupping coffee, what we are not doing is an objective analysis, in the way a geologist might analyze the hardness of a rock or a chemist might analyze the chemical compounds in a beer. Rather, coffee cupping brings together the world of the objective—the coffee—and the subjective—the tasting of the coffee by an individual human subject—and out of this synthesis is borne “cupping notes.” So when I taste “musty, cocoa powdered over-ripe strawberries with notes of smoked chocolate and cardamom,” I am basically saying, “When I see Marilyn, I see the one on the bottom left.” I’m sure that there will be many similarities and many differences when you taste my Wonka Blend (from which the description above came, though I didn’t publish it in quite that detail, since it sounds more unpleasant than it actually is), but there will probably be many differences, as well. The truth is, coffee tastes like coffee. Flavor associations, however, help to distinguish one coffee from another, which is no different than the premise on which the entire wine tasting enterprise is based. Coffee and its inherent chemicals are objective, by definition, but they way I experience them and the associations I make with other flavors are subjective (or, rather, phenomenological). Both are necessary and the one validates the other. But does this mean you will see the same Marilyn that I see when you approach your cup? Maybe; maybe not. The point is not to be “right,” but to be honest and consistent, so that when you read enough of my cupping notes against your own experience of drinking my coffees, you will not only be able to pick up on some of the same distinctive characteristics, but, more importantly, you will be able to anticipate the product you are getting.

So the short answer is really yes and no. Yes, when I cup coffee it evokes many flavor associations that call these alien foods and liquids and strange otherwise inedible objects to mind. And no, I do not take a sip of coffee and have to rub my eyes to make sure I am not chewing on tree bark or pipe tobacco. So relax and be as imaginative and adventurous as you desire when cupping or tasting coffee. It makes it more enjoyable and will help you figure out what it is that makes that occasional coffee really stand out, whether that be aged brie with blueberry jam or brownie mix with notes of Sweet Tarts. Whatever you come up with, just make sure you’re enjoying yourself while you’re doing it.

Cheers!

Jeremy

———–

Fn. 1. Hence Charles Baudelaire critiques Michelangelo’s statue of David—a 10thcentury B.C. Jewish King David memorialized in a Renaissance interpretation, which depicts him as a Greek themed hero standing in the buff.

Fn. 2. Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life”

Fn. 3. Glenn Ward, Postmodernism, 48.

Barista Exchange Partners

Keep Barista Exchange Free

Are you enjoying Barista Exchange? Is it helping you promote your business and helping you network in this great industry? Donate today to keep it free to all members. Supporters can join the "Supporters Group" with a donation. Thanks!

© 2025 Created by Matt Milletto.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of Barista Exchange to add comments!

Join Barista Exchange